What Can Sketching Teach Us About Leadership?

“You can’t do sketches enough. Sketch everything and keep your curiosity fresh.”

When the work you do is in the constant context of trauma, everything can feel urgent. Leaders often feel the pressure that they ‘should already know’ or ‘they should have already solved the problem.’ It’s true that there are crises where leaders have to act fast and rely on well-practiced protocols, but most often, leaders who lead in the context of trauma will find themselves working in a complex grey area where they need to navigate forward when the next steps aren’t clear or routine.

In coaching leaders who work in trauma contexts, they often voice frustration because they wanted a conversation with one of their direct reports or their teams to go better. Or they are frustrated because they have to have ‘yet another conversation’. The leaders feel the need to get it right on the first try and often think if they get negative feedback or it doesn’t work as planned, that the action was incorrect. What if you could instead reframe these conversations as ‘sketches’?

In my training as a psychologist, we were taught over and over that healing wasn’t an event, but instead, an ongoing conversation. We learned that making a mistake or getting it wrong with a client didn’t mean the end, but rather an opportunity for both therapist and client to learn something new, and perhaps strengthen the relationship. As a therapist, I would have a chance to correct myself or try again, and the client could clarify what they meant — which often had them see it a different way, or understand it better. And all of this strengthened healing.

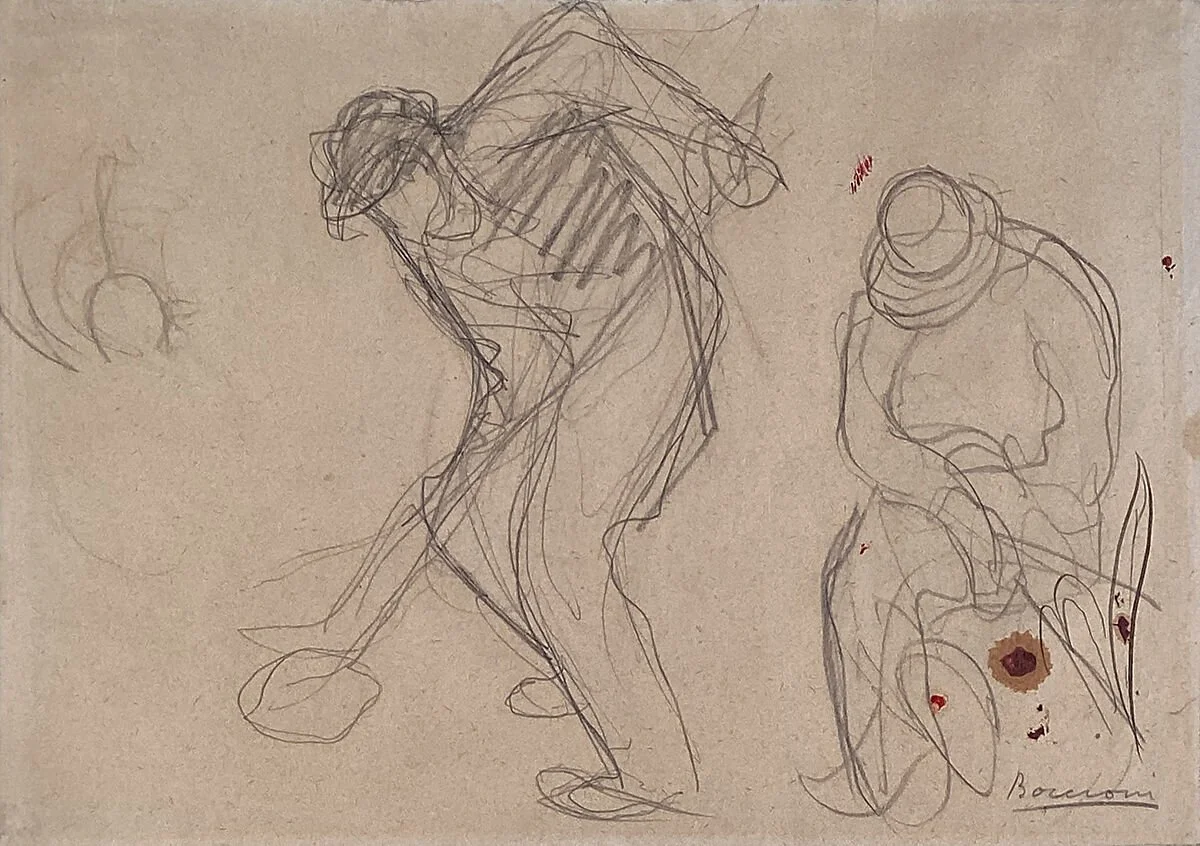

Leaders often think of the outcome or finished product — they think of the painting done, framed, and hanging on the wall. But artists know that all paintings begin as sketches or studies. When I go to art exhibits, I actually enjoy the sketches more than the finished paintings. In the sketches, I can almost see the artist thinking, I can see their humanness — where they corrected themselves or tried again. And I can see their perspective and the changes in their perspective as the work moves forward.

When artists sketch, they are practicing. They know that it takes time and practice to see and understand something fully. They are trying to understand what they are seeing, and figuring out how to translate what they are seeing onto the page. Artists have no illusion that they will get it in one try. They are allowing themselves to try something and be open and curious about what happens. When artists sketch, they are learning. They are training themselves to see. They are training themselves to observe.

This openness to learning and a different perspective is as important to leadership as it is to art. Especially in the context of trauma. So much of healing needs a stance of openness to outcome, which is the opposite of the certainty our culture demands of leaders. Yet healing requires leaders to act in conditions that are full of ambiguity. Ambiguity requires creativity of thought and iterative problem solving. Leaders need the ability to try something and try it again. Leading through trauma is inherently a creative activity.

Explore and Practice:

Sketch

Take a situation you are in and actually sketch it! It doesn’t have to be a work of art and you don’t have to show it to anyone — just get your ideas down in images instead of words. Use different shapes or lines to depict the challenge and the people in it. Or use animals, or cars, or plants. Or whatever interests you. Using the picture you sketched, reflect on the situation and notice if you see anything differently — did you leave anything out, or add anything in that you weren’t expecting? Or talk through this situation with a mentor, coach, or peer. You can also do this as a team activity. Have members of your team sketch the challenge and see what different perspectives emerge.Reflect

If you saw your last team meeting as a sketch instead of a finished action, what would you want to revise this time? What would you add to the picture? What would you take away? What if you shifted perspective and saw it from a different point of view? Or what if you brought different materials? Come up with something that you may try differently next time.

Keep Exploring:

Check out sketchbooks on this video from the Tate Museum.

© 2025 Gretchen Schmelzer, PhD